Issue #80: Tuesday 10 June, 2025

My pace of reading is still very slow, but picking up, I think.

The subtitle of this is “A Story of Where I Used to Work”. And where Sarah Wynne-Williams used to work was Facebook. She was working there for a long time, and was close to Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg, advising them on dealing with governments around the world, doing her best to get them to do the right thing. But failing.

So her book, written after she left the company, is an expose of the thinking of the senior executives of Facebook, the lack of care and responsibility for how Facebook is used around the world, how it’s misused by governments, how much evil it can do. And it’s also a condemnation of their treatment of their staff, because she was sexually harassed by her manager, and senior management brushed off her complaints.

Facebook (or rather, the parent company, Meta) has sued Wynne-Williams over the book and has succeeded in preventing her from promoting it in the U.S. All of which really is why you should read it. If they don’t want you to read it, then you should read it. Good rule.

Nick Harkaway is the pen-name of Nicholas Cornwell, the son of David Cornwell, better known as “John Le Carré”. In this book Harkaway attempts to add a new story to Le Carré’s spy novels, revisiting the character of George Smiley and the British spy headquarters of the Circus.

I think he does a good job, an excellent homage to his father’s legacy. Good story, interesting plot, great recreation of the characters like Smiley, Control, Peter Guillam, Connie, Bill Hayden, Tony Esterhase. It’s fitted very carefully into the timeline of the Circus and Smiley’s life. I liked how Harkaway shows the deep feelings of regret and guilt which Smiley has about the death of Alec Leamas (at the end of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold) and thus his distaste about having to work again with the Stasi double-agent Mundt.

There’s a really interesting Author’s Note by Nicholas Cornwell. I was fascinated in particular that he says that Smiley’s character had actually been influenced in his father’s mind by the portrayals of the character by Alec Guiness and Gary Oldman in the TV series and movie. Harkaway says:

I grew up with George. His presence, in various forms, was a friendly ghost at my table. First there was my father’s George, voice tight and sometimes raised in outrage, then a moment later coming from the gut to deliver truth, however dark. Next there was Sir Alec Guinness’s version, soft, wayward and thoughtful, as if genius could only ever step briefly from fog. Michael Jayston read Smiley in an abridged audiobook, and I listened to the cassettes every night to fall asleep. Then later my father read his own book in the same format, his cadences now mingled with Guinness’s – which was, he said, why he couldn’t write as many books into the sequence as he’d originally intended. The external Smiley had supplanted the one in his head. Much later again there was Denholm Elliott, then Gary Oldman, and others in different settings and all of them echoed in my ears as I sat down to see whether I could fit some sort of story into that ten-year gap between The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

On the down side, in my view Harkaway is definitely not the prose stylist that his father was, and doesn’t quite have his father’s skill in delineating character through action, which I always thought was worth noting. For example the start of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy when we learn almost everything worth knowing about Jim Prideaux by the arrival of his Alvis and caravan at the school where he’s going to teach, or the way he captures the character of Maria Ostrakova at the start of Smiley’s People by the way she walks home with her shopping. Harkaway doesn’t quite have that literary edge to his writing.

On the other hand it’s clearly unfair to expect Harkaway to be his father. We can be grateful that he has written this book and allowed us to revisit beloved characters and environments from his father’s books.

The Last Song of Penelope is the final book in the author’s trilogy The Songs of Penelope, a feminist re-telling of the story of Odysseus from the epic poem by the ancient Greek writer Homer.

The overall approach is to take the well-known story and look at it not from the point of view of the male heroes well-celebrated by the poets, but from the point of view of the women of the story, and specifically from the point of view of Penelope, the wife of Odysseus, whom he left twenty years previously to go off to fight at Troy.

My review of the first book, Ithaca is here and of the second book, The House of Odysseus is here. Each of the books is narrated by a different Greek goddess. In Ithaca it is Hera, wife of Zeus and patron of all wives and mothers. In The House of Odysseus it is Aphrodite, goddess of love (who tells an entertaining tale of how Paris came to be promised the affections of Helen). In this final book, the tale is told very convincingly by the goddess Athena, and we get some very interesting insights into her thinking and personality.

In Homer’s poem, Penelope is a largely passive creature, whose only claim to fame is to resist the claims of the many suitors to her hand who have gathered in the palace. In North’s very plausible re-telling, however, she has to take on the role of the queen of the island, required to manage its resources and people and defend them from attack, forced to do this largely behind the scenes since that is not seen as a suitable role for a woman. And she has had to do this for twenty long years. It’s not just Penelope herself: she recruits the women of the land to assist her, and creates a secret army of women for their defence. Remember that all of the able-bodied men of the island left twenty years ago with Odysseus and all that are left are men too old to fight, or boys yet not grown enough to take up arms.

In this final book, Odysseus finally returns, at first keeping his identity secret until the moment when he reveals himself and slaughters the almost 100 suitors in the palace. The author points up how unlikely this story is, and has Penelope and her maids tip the balance in Odysseus’ favour, though of this he remains unaware. But after the slaughter, which Penelope points out was extremely unwise, Odysseus does not receive the welcome from his wife which he has been expecting, particularly not after he has three of her beloved maids killed simply on the word of an embittered old woman who accuses them of immorality. Nor is the ending of the story as clean as Homer would have us think, but comes perilously close to disaster, again saved only by Penelope’s ingenuity and steadfastness.

I have really enjoyed this whole trilogy, very cleverly done, and generating a great deal of food for thought.

I have produced a lot of books, including many “classics” for the Standard Ebooks organisation. My rate of production has dropped off a lot the last couple of years for reasons you can probably guess, though I’m still working on titles. Here’s one particularly memorable novel I did:

Review written in April 2021

Daniel Deronda, published in 1876, was the last novel of Mary Ann Evans, who wrote under the name of George Eliot.

The novel deals with two major characters whose lives intersect. One of these is a spoiled young woman called Gwendolen Harleth who makes an unwise marriage to escape impending poverty; the other is the titular character, Daniel Deronda, a wealthy young man who feels a mission to help those who are suffering.

During her childhood Gwendolen’s family was well-off and she lived in comfort and was indulged and pampered. But the family’s fortune is lost because of an unwise investment, and she returns to a life of near-poverty, a change which she greatly resents both for herself and for her widowed mother. The only escape seems to be for her to marry a wealthy older man who has been courting her in a casual, unemotional way. This marriage turns out to be a terrible mistake.

Daniel Deronda has been raised by Sir Hugo Mallinger as his nephew, but Daniel has never discovered his true parentage, thinking it likely that he is Sir Hugo’s natural son. This consciousness of his probable illegitimacy moves him to kindness and tolerance towards anyone who is suffering from disadvantage. One evening while rowing on the river Thames he spots a young woman about to leap into the water to drown herself. He persuades her instead to come with him for shelter to a family he knows. The young woman turns out to be Jewish, and through trying to help her find her lost family, Deronda comes into contact with Jewish culture and in particular with a man called Mordecai, who has a passionate vision for the future of the Jewish race and who sees in Daniel a kindred spirit.

The lives of Gwendolen and Daniel come into contact at many points, and Daniel’s kindly nature moves him to try to offer her comfort and advice in her moments of distress. Unsurprisingly, Gwendolen misinterprets Daniel’s attentions to her, which leads to her further distress.

In Daniel Deronda Eliot demonstrates considerable sympathy towards the Jewish people, their culture, and their aspirations for a national homeland. At the time this was an unpopular and even controversial view. A foreword in this edition reproduces a letter Evans wrote to Harriet Beecher Stowe, defending her stance in this regard. Nevertheless, the novel was a success, and translated almost immediately into German and Dutch and it is considered to have had a positive influence on Zionist thinkers.

Daniel Deronda has been adapted into the form of films (the first in 1914), and into television series, most recently by the BBC in 2002, a series which won several awards.

Again, I’ve been watching a lot of films and TV shows. I’ll therefore only give you brief reviews (with one exception)

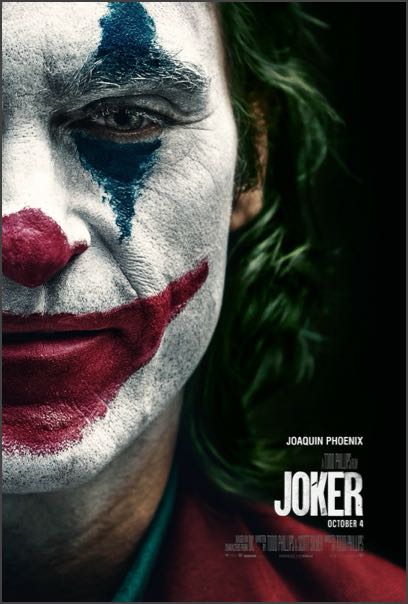

A really excellent take on the concept of the Joker character from the Batman movies, starring Joaquin Phoenix as the title character. Very much more of a psychological thriller than a comic-book adaptation. Phoenix apparently lost some 23 kg of weight to play the part, and it shows, there are times you look at his ribs showing and wonder how he managed to do it.

This was a re-watch. The movie was released in 2011, so it was very interesting to re-watch this in the light of our very real experience of COVID-2019. It’s amazing how much of it was prescient, the only major miss being that we didn’t have the level of social unrest shown in the film. But the rest of it is there: the reluctance of authorities to act quickly; the initial uncertainty about how the virus was spread; the attacks on the experts; the people making money from scaring people away from vaccines and touting bogus cures.

I decided that I wanted to see the latest Mission Impossible movie (Final Reckoning, episode 8) because it was on at my local cinema, so I thought about re-watching some of the previous episodes. I discovered that Apple had a really good deal on a “boxed set” of episodes 1 through 6, and a very good price on episode 7, so I bought them all and kind of binge watched them, one film a night.

Overall impression: some very entertaining action and plotting. But episode 2 (Mission Impossible II) was, as everyone seems to agree, pretty bad. Episode 7 (Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning) was pretty good, but episode 8, which I saw in the cinema, was a big let-down.

Tom Cruise is great at doing all the action stuff, famously doing many of the stunts himself (for episode 7, according to the background extra, he drove a motorcycle off a high mountain cliff no less than six times). And otherwise he does charming very well. But by crikey there is never any conviction to his supposed romantic connections with the women he hooks up with in the movies. I found the idea of his actually having any real feelings toward Rebecca Ferguson and Hayley Atwell in the last few movies completely unbelievable. It was kind of “Really? He’s now supposed to be in love with her?”

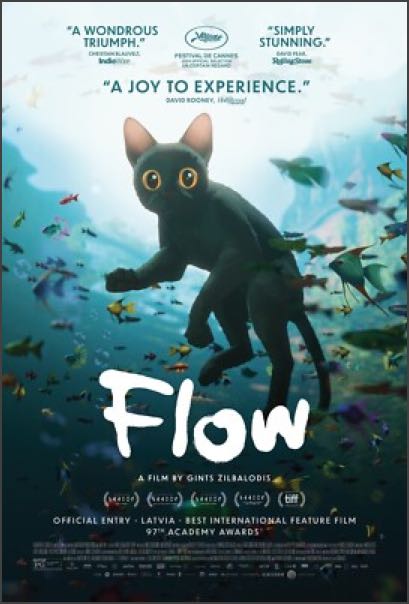

A Latvian animated movie, co-produced with French and Belgian producers. It was created entirely using the open-source Blender software, and has no human dialogue. It won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, the first independent film to do so.

A beautiful, moving film following what happens to a particular small cat and various animals she encounters along the way, as she tries to survive in a world where humans have died out. A massive inundation forces her and her companions to flee their normal locations and struggle to survive. Entrancing to watch.

Well worth seeing. Highly recommended.

Bong Joon Ho is a multi-award winning Korean film-maker, probably best remembered by English-language viewers for writing and directing the film Snowpiercer released in 2013.

His film Parasite was released in 2019. It won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and then the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2020, the first non-English-Language film to do so.

It’s been described as a “black comedy”, and I guess that’s a pretty good description. But while it’s black it’s not a dark film, at the end I gave a sad chuckle rather than feeling a sense of despair.

So what is it about? It’s set in Seoul, the capital city of South Korea. The basic story is that of the impoverised Kim family who live in a “sub-basement” flat in the poorer regions of Seoul. Everyone in the family is out of work, and they don’t have enough money to pay for Internet access (and since What’s App is the major tool for communication and commerce, this is a real problem).

Their son, Ki-Woo, has carried out his compulsory period of military service but didn’t manage to get into college. One day, however, his school friend, Min-hyuk, turns up with a gift, a mounted piece of rock which is from Min’s grandfather’s collection. He tells Ki-Woo that it’s a “scholar’s rock” which will ensure wealth. Whether that is true or not, this rock ends up playing a key role in the story.

Then Min tells Ki-Woo that he’s going overseas for a few years, and encourages Ki-Woo to apply for his job as an English-language tutor to the daughter of the rich Park family. Ki-Woo’s sister Ki-jung has great Photoshop skills and helps him forge college graduation certificates.

I won’t go into the details of the plot, I’ll simply say that ultimately, through various kinds of subterfuge, each member of the Kim family: father, mother, son and daughter, all end up employed in different roles in the Park household, getting the previous workers dismissed on various pretexts, while concealing the fact from the Parks that they are in fact all from one family.

All is going swimmingly and the Kim family are raking in heaps of money from these jobs. But then there’s a twist and it all comes undone and ends in catastrophe. I won’t spoil it for you.

But what is the film really about? Well, as Ki-Woo says frequently, “it’s so metaphorical ”.

More than anything it’s about the class structure and the vast gap in wealth and thus living standards of different parts of society. And about the attitudes of the rich towards the poor. The Park family are almost obscenely rich and live in this magnificent house designed by a world-class architect. The Kims live in a miserable “sub-basement” apartment.

I was struck by the excellent cinematography which emphasises the differences: scenes inside the Park’s house are often wide shots which emphasise the size and luxury of the place, with the screen filled from edge to edge with the interior of a room with the characters at middle-distance, or over to one side of the view. Scenes inside the Kims‘ flat are close-up, tight, almost claustrophobic.

We also have a great deal which tells us about the attitude of the Park family, particularly the businessman father Dong-ik, towards those less fortunate. He says “I can’t stand people who cross the line”, meaning the social line, poor people wanting to be too familiar with a rich person.

At one point their young son, Da-song, sniffs at each of the Kim family (all of whom are pretending to be strangers to each other) and exclaims that they all smell the same. Later, Dong-ik says “it’s the sub-basement smell” and complains of the smell of the Kim family father who is now employed as his chauffeur, “he smells like an old radish”, and says “you sometimes smell it on the subway. People who ride the subway have a smell”, to which his wife simply comments “I can’t remember the last time I used the subway”. The sense of contempt, almost of disgust, is strong.

Part of the metaphor, of course, is where the two families live, not just their dwelling, but the location of that dwelling. Getting to the Park house involves climbing up a steep slope. Late in the film there’s a severe storm and a deluge of rain. That water of course rushes down through the city to its lowest levels, and floods the region where the Kim family lives, inundating their apartment. Hundreds of people are evacuated and have to spend the night sleeping together miserably in a school gym. By contrast, the following day, when the Parks summon all of the Kims to help with their son’s birthday party, they are commenting on how wonderful it is that the rain washed away all of the pollution so that it’s a gorgeous sunny day for the party. Young Ki-Woo, looking out at the gathering of rich people at the party, realises that he can never fit in with such people.

As I mentioned before, there is a twist and things go really, really badly wrong for all concerned. While they are lying in the gym, Ki-Woo asks his father about his plan to fix things. But his father says there is no plan. He says something like:

You know what kind of plan never fails? No plan at all. No plan. You know why? If you make a plan life never works out that way. Look around us. Did these people think “Let’s all spend the night in a gym?” No. But look now, everyone sleeping on the floor, us included. That’s why people shouldn’t make plans. With no plan, nothing can go wrong and if something spins out of control it doesn’t matter. Whether you kill someone, or betray your country. None of it f~~~~ matters. Got it?

Look, I loved this film, it’s really enjoyable to watch. Highly recommended.

Other recent things, no time or space to talk about them at length this time:

If you’d like to make a modest contribution to my efforts in this newsletter, I’d love it if you would buy me a coffee.

Want to comment? Please send an email to:

© Copyright 2025 by David R. Grigg

and licensed under Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 4.0.