Issue #72: Wednesday 28 August, 2024

I’m running a little late with this issue, so there are a number of books to talk about.

A Pale View of Hills is Ishiguro’s debut novel, published in 1982. He went on, of course, to write many other novels and won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature.

I have to say that I don’t really understand this book, but perhaps that’s the author’s intention! It’s certainly a book which makes you think and puzzle over for days after you’ve finished it. I see I’m not alone in my reaction, as according to Wikipedia the New York Times called it “infinitely… mysterious”.

The story is told from the first-person point of view of Etsuko, a Japanese woman who married an Englishman and is now living alone on a large estate in rural England. As the book opens, she is being visited by her younger daughter Niki. Etsuko is grieving the death by suicide of her eldest daughter Keiko a few years previously. Niki’s visit spurs Etsuko to recall her life in Nagasaki in Japan a few years after the end of the Second World War (and of course, after the atomic bombing of the city).

In particular, Etsuko thinks of her interactions with a woman she befriends called Sachiko and her young daughter Mariko. Sachiko is living in a little cottage next to a river, on the other side of a large area of waste land. She has a relationship with an American soldier called Frank, who has promised to take her back to America, but this promise seems likely to be betrayed. Mariko is a strange, withdrawn child who we learn later saw some terrible things in the aftermath of the bombing. But Sachiko pays the child little attention, doesn’t appear to send her to school, and leaves her alone for long stretches of time. She brushes off Etsuko’s frequent concerns about Mariko.

The strangeness of the story is that it is clear there are strong parallels between Sachiko and her disturbed daughter and Etsuko and her daughter Keiko, who as a young adult became increasingly withdrawn and eventually committed suicide. And between Sachiko’s foreign lover and promise of living in America and Etsuko’s actual second marriage to a foreigner and subsequent residence in England. The narrator however never explicitly draws these parallels but leaves it open to the reader.

As the narrative progresses, there is a growing sense of unease, and disturbing events happen. We learn that there have been a number of child murders in Nagasaki, young children found battered to death, a girl found hanging in a tree.

There comes a point at the end of Chapter Ten which literally stopped me in my tracks (I was listening to the book as an audiobook while I was on my morning walk). I wound the audio back ten seconds or so to listen again. What did she just say?

You are left with many questions. Clearly Etsuko is an unreliable narrator, but it’s all but impossible to tease out just where her story varies from reality, what part of her recollections might be true and what false. Is Sachiko really Etsuko herself, and Mariko a younger Keiko? And how much of what really happened has been left out or distorted? Some of the possibilities are really disturbing.

Fascinating, intensely puzzling, but very good. An amazing writer.

Note: As indicated above, I first listened to this as an audiobook, but after I had finished I had to go out and get hold of an ebook version, so that I knew how to spell all of the character’s names correctly! And also so I could re-read a few sections of the book as I pondered over its meaning. Not easy to review material in an audiobook.

This is an entertaining thriller by an Australian author. It’s Rose Carlyle’s second novel, following The Girl in the Mirror, which I haven’t read, but which received considerable acclaim.

This novel is told (mostly) from the first-person point of view of a young woman, Eve Sylvester. Shortly after the start of the book, Eve discovers she is pregnant, but she when she approaches the rich family of her boyfriend, who died in a car accident, they shun her, treat her coldly and offer no help. Eve is an orphan, so has no family of her own to support her, has few skills and no savings, so she is becoming desperate.

While she’s grieving her boyfriend in the cemetery, an older woman approaches and strikes up a conversation. It seems like a gift from Heaven when this woman, Zelde, tells her that her wealthy employers, Christopher Hygate and his wife Julia, are looking for a nanny for their baby, and all but offers her the job.

After Eve gets the job and moves to the island off the coast of Tasmania where the Hygates have their mansion, the story takes many unexpected twists and turns, which I won’t reveal, other than to say that this apparently heaven-sent job turns out to be anything but. Zelde and the Hygates have deceived her. Their deception goes much deeper than it first appears, and keeps on getting deeper. A high level of tension is kept up throughout as Eve tries to escape from the coils in which she finds herself.

There are some touching scenes as the story jumps six years forward shortly after Eve gives birth. A focus of the book is on the strength of the bond between a mother and her child, and the extraordinary lengths she will go to protect it.

I did think that a weakness of the book was the rather pat ending in which all the bad guys get their just deserts and all the good guys triumph. I would rather have had more shades of grey, and some ambiguity, but perhaps that’s just me.

Setting that aside, I did enjoy the book, which kept me turning the pages, and I’d be happy to read anything else the author writes.

This book will be published by Text Publishing on 1 October 2024.

I enjoyed reading this informative and very interesting book about recent archeological discoveries in Britain (where it almost seems as though if you dig up a few spadefuls of dirt almost anywhere you’ll come across a Roman coin, an Anglo-Saxon burial or the ruins of a Medieval building).

This particular book focuses on life in Britain in the first millennium (that is, 1 AD to 1000 AD): the period when it became a Roman province, and then what happened to its people after the Roman Empire declined and its troops were withdrawn from Britain.

What becomes clear from reading the book, though, is that it can be extremely hard to properly interpret what archeologists find when they dig. Alice Roberts is an osteo-archeologist—her scientific interest is primarily what the bones of the dead can tell us—but she’s also extremely interested in trying to imagine the lives of these people and what their culture was like.

However, she tells us again and again that it’s rash to leap to conclusions. We really don’t know what people were thinking, when for example, they buried many perinatal babies in or close by their settlements. Infanticide when there was no form of contraception available? Ritual? Epidemic of fatal childhood illnesses? Or what they were thinking when they buried people with their skulls removed and placed between their feet. Execution? Fear of the “walking dead”? We just don’t know.

A particularly interesting chapter at the end of the book, titled “Belonging” re-examines the the previously accepted story (which I was taught at school) that after the Romans left, Britain was invaded and conquered by the “Anglo-Saxons”. Well, perhaps. That’s the story told in historical accounts such as those of the Venerable Bede (672 to 735 AD), but such accounts are now being looked at with considerable scepticism. Instead, it seems there had always, even during the Roman period, been a lot of trade between Britain and Northern Europe, and the apparent “invasion” of Germanic peoples may have been more to do with increasing trade and intermarriage between the British and those from the Continent, leading to a strong cultural merging rather than violence. The archeological record is by no means clear, but tends to support these new ideas.

A very worthwhile read, but perhaps of less interest to you if you weren’t born in Britain as I was, and was taught a particular view of British history.

This was another production I did for Standard Ebooks.

Perhaps I should explain what I do in producing these titles. As well as many other tasks, such as finding a cover which is provably in the U.S. public domain (often a difficult task), I need to carefully proof-read the book, which in this case is based on a transcription done by the folk at Project Gutenberg. I’m looking for typos, bad punctuation, and things which need to be specially formatted such as letters. I’m reading the book in “raw” HTML format with all the angle-bracket tags such as <p> and <em> and <abbr> etc. This needs very close attention and takes quite a while, particularly with a long work such as this one (330,000 words!). And one of the final tasks is to write a description of the book which will appear on the S. E. website. Here’s what I wrote for this book:

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby tells the story of the eponymous hero and his sister Kate after the death of their father leaves them and their mother destitute and dependent on the support of their uncle Ralph Nickleby. The latter is a cold, hard man whose only interest is in amassing money and influence, and who has no empathy for the plight of his brother’s wife and children. Though he is very rich Ralph offers them almost nothing, other than arranging for Nicholas and Kate to be employed in degrading jobs and for their mother to live in a near-derelict house he owns. This disregard eventually turns into pure hatred on Ralph’s part after Nicholas thwarts some of his schemes. However, Nicholas and Kate eventually free themselves from Ralph’s malign influence and make a success of their lives.

An important secondary character in the book is Smike, a boy in his late teens who Nicholas encounters at Dotheboys Hall, a Yorkshire school where Nicholas has been employed as an assistant teacher. Smike has been reduced to a pathetic wretch by years of ill-usage and half-starvation by the schoolmaster Mr. Squeers. Nicholas, taking pity on the boy, eventually leaves the school with Smike, who becomes his constant companion and friend in their subsequent adventures.

Nicholas Nickleby was the third novel written by Charles Dickens. Like his previous two novels, it was originally published in serial form, appearing in Bentley’s Miscellany over 19 monthly installments from 1838 to 1839.

One of the most popular of Dickens’ novels, Nicholas Nickleby is full of a variety of interesting and amusing characters and incidents. It has been the basis of a great many successful adaptations for theatre, film and television. A stage adaptation by the Royal Shakespeare Company was videotaped and won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Miniseries in 1983. A film version directed by Stephen Whittaker for television in 2001 won a BAFTA award.

You can get a free ebook of this title here.

Another review from before I was publishing Through the Biblioscope.

(review written October 2019)

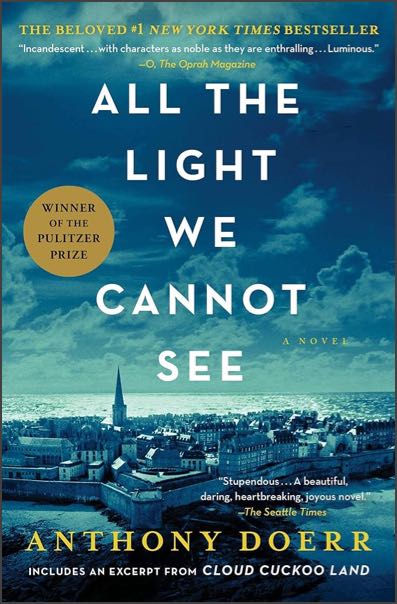

This won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2015.

Set during the Second World War, it tells the stories of two young people: Werner, an orphaned German boy who is raised with his sister Jutta in an orphanage in a place called Zollverein, a coal-mining district near Essen; and Marie Laure, a blind French girl whose father works in a museum in Paris.

Werner’s future seems destined to be that of a coal-miner, until his intelligence and aptitude for electronics and radio become evident. He is eventually recruited by the Nazi Party and sent to a special school to be trained to serve the Reich.

Marie Laure became progressively blind at the age of 6. Her mother is long dead, but her father, who is a locksmith and a craftsman raises her tenderly and creates mechanical puzzles for her to solve, together with a physical model of the surrounding buildings so she can become sufficiently familiar with the district that she can never become lost.

All of this changes when war breaks out. Marie Laure and her father are forced to flee Paris as the Germans invade, eventually ending up in a coastal town called San Malo. Her father has secretly been entrusted with a precious jewel from the museum, reputed to have miraculous powers of healing of the person who possesses it, and at the same time casting a curse on those around that person. Part of the plot of the book is the frenzied search for that jewel by a German officer who is suffering from cancer.

The story is about how the lives of these two main young characters become intertwined and how in the ultimate crisis, they save each other. But fear not, they do not fall in love and live happily ever after. The ending is much more nuanced than that.

Beautifully written throughout. This is probably the best book I’ve read all year.

Comment on Issue 71

12 August 2024

Mark Nelson

If you’d like to make a modest contribution to my efforts in this newsletter, I’d love it if you would buy me a coffee.

Want to comment? Please send an email to:

© Copyright 2024 by David R. Grigg

and licensed under Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 4.0.

Probably a bit late in my career to reap the rewards of improving the clarity and style of my writing...

A few years ago the university decided that all three-year degrees had to include a "Capstone project" in their final year. It was not clear what this meant, but the vague intent was that a capstone project in degree X prepares students for their post-graduation professional work in discipline X.

One of the components of the capstone project in mathematics is an introduction to professional writing. When I came to Wollongong in 2003, I ran a computer lab for first-year students in which they had to carry out projects and write up their findings for a general audience. This was very unpopular. Plenty of students told me that the joy of mathematics was that you did not need to know how to write in sentences or paragraphs. Thankfully, such attitudes have almost died out. Writing in the mathematical sciences is a little different to general writing as it has its own conventions. However, many mathematicians/statisticians working in industry are working for non-mathematicians/statisticians so they need to know how to express ideas in non-technical English. It's much more important for them to write well then they realise. However, there isn't much time in two-hours a week for thirteen weeks to go through the basics of good writing.

A roundabout way of saying that if I don't get a copy for myself, that I should order a copy of Dreyer's English for the library. Oh, that's unusual. Someone has already ordered a copy for the library. Oh, that's even more unusual. It's available as a hardcopy, not as a ebook. It's sitting on the shelves as I type...

It's not sitting on my desk as I type... Usually, I'd glance at a book like this, stick it on my shelf of books I've taken out of the library, keep it for a couple of years, and perhaps glance at it before eventually returning it. This time. This time. I read the New Introduction and the Introduction. At the very least I will read one chapter every time a new issue of Biblioscope wings its way to me.