Issue #67: Sunday 9 June, 2024

Once again, I haven’t been reading at my usual pace, for reasons explained last time. I hope to get back to my usual rate of book consumption by next issue.

The author of this book, Elizabeth Tasker, is a British astrophysicist who works primarily in the area of computer simulation of star formation. The Planet Factory, her first book, was published in 2017, which makes it a little behind our current knowledge. Nevertheless, there was a great deal in it which was completely new to me, and I found it absolutely fascinating.

Now, this is a bit of a digression. I want to start by admitting that I’m old. I’ll very shortly be 73 years of age. Younger people may therefore have trouble understanding how profound a change has occurred in our knowledge of astronomy since I was at school, sixty-odd years ago. But I’d like to take you through it from my point of view and hope not to bore you in the process.

I clearly remember looking with fascination at photos of the planets in some kind of illustrated science book when I was in primary school. The best photos of Jupiter and Saturn in the book were very fuzzy ones in monochrome, showing little detail. Yes, you could see that there were bands of different shades of grey and a darker big spot on Jupiter; and the shape of the rings of Saturn were obvious. But that was it.

At school, we were taught a theory about how the Solar System came to be: another star passed close to the Sun and drew out a long filament of matter from its surface, like a long hot sausage, thicker in the middle than the ends. This then broke up into the individual planets. Obviously, such an event would be an extremely unusual and unlikely one, and therefore planet formation would be a very rare occurrence. This is the Tidal Theory proposed by Sir James Jeans in 1917, and by the time I was taught it, it should already have been considered well out of date; but education lags behind current thinking as a matter of course. I was also taught that the craters of the Moon were those of now-extinct volcanoes. The idea of them being impact craters was yet to be accepted.

Naturally, since I’ve always been interested in science, as I grew older I kept on top of most of the latest thinking and knowledge, and was thrilled by the incredible photographs taken of the outer planets and their moons by the Voyager probes in the early 1980s. Where previously we had only had fuzzy photographs taken by Earth-based telescopes, on which the moons of these planets were really only dots of light, now we could see close-ups in great and fascinating detail.

When I was young, there was no evidence that there were planets around any star but the Sun (making the Tidal Theory at least plausible, I suppose). Today, because of instruments like Kepler, we know of many thousands of exoplanets, and all the evidence leads us to believe that almost every star in the sky must have its own family of planets. Even more incredible, in many cases we’ve been able to determine the size, mass and sometimes even the atmospheres of these distant worlds.

The Planet Factory discusses these discoveries, and the rapidly-developing ideas about how planets are formed, in considerable and very interesting detail. As more and more exoplanets were discovered, almost every new discovery meant that the current theories of how planets form had to be modified and in some cases completely discarded. What is becoming very clear is that our own Solar System, which we had naturally assumed to be a typical arrangement of planets, is far from typical. In fact based on what we see around other stars, it may be quite unusual. Some of this perhaps is down to a bias towards the kind of planetary systems we can most easily discover, but by no means all of it. And our understanding of how the Solar System itself formed has undergone many changes: new ideas suggest that the giant planets of Jupiter and Saturn may have at one point migrated inwards much closer to the Sun, and only later moved outward again and found their current apparently settled positions. There may well have been a gas giant of the size of Neptune or Uranus which was ejected altogether from the Solar System and now wanders, lonely as a cloud, in the depths of space.

The author then looks at trying to find a “second Earth”, an Earth-like planet around another star in the temperate zone which would allow liquid water and life on its surface. The book shows how tricky and complex this search is, and will continue to be. Planets are extremely complicated things, and as the author says firmly at one point: “an Earth-sized rocky world does not equal an Earth”. As we’ve found with the bodies in our own system, it has been all but impossible in advance to predict what the surfaces of planets and moons would be like in any detail. Apparently minor differences in geology, in composition, in position, in illumination, can create extremely different results on planetary surfaces.

There are times in the book where the level of detail of discussion of alternate theories becomes rather too much too quickly, but overall I really enjoyed what I learned.

Recommended.

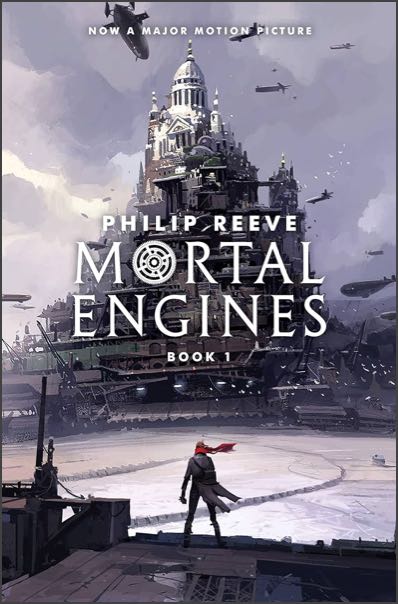

This was a re-read on my part. I first read it, and its sequels, in 2009 to 2010, and I’ve been nursing a desire to read them all again for a while now. After some recent stresses on the domestic front (as I alluded to last issue), I was just looking for an easy, “comfort read”. And this was it.

The four books in the “Mortal Engines Quartet” are aimed at a middle-school level, but as I’ve often discussed before, I really enjoy many books pitched at that age-group, As W. H. Auden once said: “There are good books which are only for adults. There are no good books which are only for children.”1As quoted in Katherine Rundell’s wonderful book Why you should read children’s books, even though you are so old and wise (2019).

So, with these books you have to start with the fact that they have a completely wacky, almost absurd starting premise: the idea that far in the future, on a devastated Earth, cities have become mobile on vast traction engines. Not only that, but larger cities prey on smaller cities and towns, in a town-eat-town world dictated by the laws of “Municipal Darwinism”. There’s quite a thread of ironic humour throughout. I laughed out loud when the main characters first encountered the pirate suburb called “Tunbridge Wheels”.

Such juvenile humour aside, there are some very dark threads to the narrative.

In this first novel, Mortal Engines, we are introduced to young Tom Natsworthy, an Apprentice Historian working in the museum of London, one of the oldest and greatest of traction cities, as it bears down on a fleeing town, mechanical jaws gaping wide, ready to tear apart and repurpose all of its victim’s components.

Tom’s hero is Thaddeus Valentine, the Chief Historian of London: explorer, adventurer, scholar. While carrying out a trivial errand, Tom encounters the charming Valentine, who speaks to him in a friendly fashion. Moments later, however, Valentine is attacked by a masked girl wielding a knife. Tom leaps to stop her, then chases her as she attempts to escape. What happens subsequently throws Tom quite literally out of his comfortable but boring life aboard London, and into a much wilder world on the ground and eventually in the air, all in the company of the would-be-assassin masked girl, whose face when revealed shows a hideous scar and one dead eye. At first the girl is furious with Tom for thwarting her attempt on Valentine’s life. Her name, we discover, is Hester Shaw and we learn that she has very good reason to hate Thaddeus Valentine.

There’s plenty of interest in the rest of the book, as London heads off to new hunting grounds, equipped with a deadly weapon recovered from ancient technology, and Hester and Tom grow to know each other while suffering through a series of extraordinary and perilous adventures. There’s romance and tons of excitement, and some clever world- and society-building. I enjoyed re-reading it a lot, and I’m sure many early- to mid-teenagers would love it, too.

Note: I just love the covers of this series in the Scholastic editions published in 2018. If I didn’t already own all the books I’d rush out and buy them all just for the covers.

I’m current watching my way through Dark Matter on Apple TV+, based on the SF novel by Blake Crouch. Very well done, so far. Given that Blake Crouch is heavily involved in the television production, it’s interesting how far that it deviates (mostly in positive ways) from the original novel.

As quoted in Katherine Rundell’s wonderful book Why you should read children’s books, even though you are so old and wise (2019). ↩

Comment on Issue 66

26 May 2024

Bruce Gillespie

---

Yes, "moving" is a good adjective to describe Bookbinder. Peggy's love and care for her sister, and her realisation that Maud has her own life to lead; Peggy's troubled relationship with Bastian; and the impact of the war on all of the characters: yes, all of that is very moving.

—David

Comment on Megaloscope 12

3 June 2024

Mark Nelson

Your review of Natasha Pulley's The Half Life of Valery K made it sound very intriguing. Not so much that I put it down onto my list of books that I will mostly never read, thrillers not being a genre that I usually read. Agnes Ravatn's The Bird Tribunal also sounded fascinating, as did the Reykjavik Noir trilogy. So why did I single out Pulley's novel? Could it be as simple as it being the first one that you reviewed? Maybe. But reading your review reminded me that just over forty years ago I read One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. (A book that I should reread.)

At first I started reading your review of The Absolute at Large with a degree of trepidation. I don't have a concrete reason for this, except a suspicion that Karel Capek was mentioned in a recent issue of N'APA and the discussion of his work was off-putting. (What's the world coming to when you can't really remember what you read in the other apa that you contribute to?) OTOH, you made The Absolute at Large sound very entertaining.

(Regarding A History of the Bible) Like you I am not a Christian, though I was baptised in the Lutheran Church of Finland, which I've just discovered "is one of the largest Lutheran churches in the world", and attended a Church of England infant and Junior school. Like you, I think, I am fascinated in the history of Christianity. I don't remember the "best" book that I've read on the history of Christianity, it's been in a box in the garage for eight years. If I unpack that box after our move I'll let you know it's title. What I took from this book was that if you look at the Christian faith on the time span of years, decades, and sometime even centuries it is an immovable object. But if you look on longer time-scales it's like the ever shifting tectonic plates. Further, as we move away from the birth of Christ seismic shifts in doctrine occur with an increasing frequency. (Perhaps that should have been obvious to me, but prior to reading the book with no name I did not have the right perspective on this.) I have added this book to the list of books that will mostly never be read.

(Regarding Murder at Mansfield Park) Not long after I wrote my last loc I was in the local library when I walked down an aisle I don't usually visit and spotted Linda Berdoll's Mr Darcy Takes a Wife, described as "the most salacious and controversial Jane Austen sequel ever". Despite the fact that it was published by Penguin I walked on by, only stopping to take a photograph of the cover so that I wouldn't forget to report this back to you. I wonder how many Pride & Prejudice sequels have been published?

I probably should reread Emma, and perhaps I will when I retire... As it's thirty years since I last read it I don't remember why I disliked her character. I have a feeling that rather than being misguided in her interference in the affairs of others I thought she took a more active pleasure in it. I have seen Clueless a couple of times and agree that it is a lot of fun. I'm not very familiar with all the ins and outs of the story, I probably should buy a copy...

Some paragraphs ago I mentioned N'APA. In Intermission 140, Ahrvid Engholm provided an account of a panel organised by the Writers Union of Sweden, on December 11 2023, to discuss science fiction. I thought you might be entertained by the following observation.

"((During the panel)) It was argued that sf is not suitable for audiobooks, something that otherwise is growing rapidly at the moment. (It will grow even more when the audiobook publishers program AIs to narrate.) The reason was stated to be that sf requires the ability to think and reflect, and it doesn't go as well when the book enters through the ears."

---

To answer your last question first, I think this attitude to SF in audiobook format is complete nonsense. I've listened to many an SF work in audiobook format and enjoyed and appreciated them all. I don't see why stopping to think and reflect after listening is any different than doing the same after reading the same amount of a book. You get the same sort of nonsense said about ebooks as well as audiobooks. It's a kind of printed-book elitism.

I'm not sure why a discussion of Karel Čapek's works would be off-putting. I don't think you'd call them great literature, but they are a lot of fun and often thought-provoking.

Doubtless there have been many hundreds of sequels or spin-offs of Pride & Prejudice and other Austen novels, but few of them, I suspect, are worth reading. The original is always the best.

—David

If you’d like to make a modest contribution to my efforts in this newsletter, I’d love it if you would buy me a coffee.

Want to comment? Please send an email to:

© Copyright 2024 by David R. Grigg

and licensed under Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 4.0.

It’s not often I agree with either you or Perry about many books reviewed in your respective fanzines, but I agree completely with you about In Ascension and The Bookbinder of Jericho. The Pip Williams is one of the most moving novels I’ve read during recent years.

Both of you put me onto Mick Herron, but in fact I found Secret Hours rather flat and laborious in its plotting, except the for the great chase sequence at the beginning.

Fortunately I bought as many earlier novels as I could find (three) from the Slough House series, but not in consecutive order, in The Paperback in town, and they are much more readable -- well plotted and often very funny. Read so far are Dead Lions and London Rules. I haven’t searched in Dymocks yet.

Best novels read so far this year have been A Long Long Way (2005) by my great discovery author Sebastian Barry (thanks to Tony Thomas for this tip-off); Poor Things by Alasdair Gray (much better than the movie); Snowleg by Nicholas Shakespeare (another favourite author, when I can find his books); Sanctuary by Garry Disher (one of his very best), and The Grief Hole by Kaaron Warren (truly weird).

Only 21 books read so far this year -- very different from last year. But then, Dick Jenssen somehow hung on to life during last year, but left us on 7 March. Looks as if he is going to [affect] our lives from beyond the grave for several years to come.